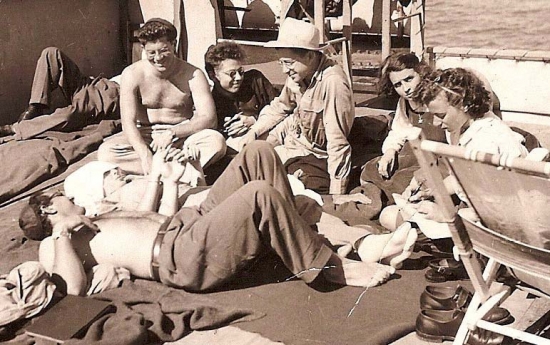

On the way to Palestine

Israel November 1947.

I was born on the Lower East side of Manhattan in 1929. My most vivid and beloved memories of childhood were in the Downtown Talmud Torah where I went after public school each day for and hour and a half of studying. Once a week there was a choir session with a teacher I worshipped named Mr. Kalb, who introduced me to the world of Jewish music.

I loved Talmud Torah, speaking Hebrew and learning Chumash (Bible) and Neviim (Prophets). When I understood enough Hebrew to appreciate the prayers, I said to them with sincerity, especially the verses, “May our eye behold Your return to Zion in compassion.” And “Next year in Jerusalem.” Anything that had to do with Zion, Jerusalem, G-D, Am Yisrael, Eretz Yisrael all connected up for me.

The clincher was a little blue and white JNF box embossed with a map of Eretz Yisrael which was placed on Miss Morgenlander’s desk. The map made Eretz Yisrael real – like the countries in the geography book – where people called “Halutzim” lived and worked. They needed my pennies to help them build the land.

Miss M. was beautiful. She had gorgeous blonde curls which she combed one by one before the bell rang, and she told us whatever she knew about Eretz Yisrael. I knew that Eretz Yisrael was where I belonged.

When I grew a bit older, I found my place in a group that talked about Eretz Yisrael and halutzim. When I was seventeen, a friend who had fought in the American army told me he was going to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem for a year’s study under the G.I. Bill of Rights.[1] “Wow,” I said, “I wish I were you!”

“Why not?” he asked. “All you need is money and two years of college to study there.” “I have one year of college behind me,” I said to myself, “and money I can earn.” I got myself a job teaching in Talmud Torah and a summer job waiting on tables in Saratoga Springs, a popular upstate New York vacation spot. I completed another year of Brooklyn College, and the following October 1947 found myself on board a Liberty ship[2] named Marine Carp and on my way to Eretz Yisrael to fulfill my life’s dream.

Looking over the railing, I suddenly realized where I was and what I was doing – leaving everyone I knew and loved, and going to a place where I knew nobody – alone, alone. Where would I be? For how long? “what am I doing here?” I asked myself, and burst out crying hysterically. A kind, middle-aged man standing near me said, “why should you cry? You’re going home. One day all those people down there on the dock will follow you.” His name was Yitzchak Gross, a shaliach (emissary) from Kibbutz Chafetz Chaim. He must have been a descendant of the Prophet Elijah, because every person in the group that accompanied me to the boat has come to live in Israel.

The boat was supposed to leave on Saturday, so the Sabbath observant passengers boarded on Friday. We formed a closely-knit group, eating together on Friday night, sharing the food we’d brought from home. Yitzchak made Kiddush and we were a family throughout our trip. When we left the ship after two weeks at sea we exchanged addresses, promising to visit each other in the different cities and kibbutzim. So, for me, an eighteen-year-old girl on her own for the first time in her life it was an “easy passage” in every sense of the word.

In Jerusalem I shared a room near Mea Shearim with two Israeli girls in a student boarding house which was separated from the adjacent British encampment by barbed wire. Almost every night, boys from the Irgun (the Revisionist Zionist militia) would come and shoot into the camp from the front of our house, and then disappear.

While working one evening in the students’ restaurant in the center of town with two other girls, I saw two men run up the alley opposite the front door after throwing a bomb into the officers’ club nearby. There was an immediate curfew. The street filled with British soldiers, several of whom came into our restaurant. Being young, daring and stupid, I was insolent to them and demanded an escort home so I wouldn’t be shot. It worked! My chutzpa got me an escort and enabled me to take the other girls home with me for the night.

On November 29, 1947 less than a month after I had begun my studies at the Hebrew University, Israel was partitioned and the next day the Arabs started the war. The university closed down so that the students could either go out and fight or return to their homes. A bomb fell in my closet and ruined most of my clothes. My roommates returned to their homes in Tel-Aviv and Haifa, and I went to a store-cum-recruiting center to join the army. A friendly man sporting a beret asked me where I lived, and after telling him my story and how my dorm had closed down, I told him that I expected to live in the army now. “There’s nowhere to live in this new army that’s being formed,” he told me. “The soldiers show up for training or go out fighting, and then they go home to sleep.”

He suggested I meet a friend of his, the principal of a religious seminary for leaders of Youth Aliya which was located on the western border of Jerusalem in Bayit Vegan. I could join this group which continued to study while serving as the western outpost. We would have military duties and would be an official fighting unit serving in the New Jerusalem Division. (Little did I dream that forty years later this army duty would be worth three points added to my pension).

I stayed at the seminary for almost a year, doing guard duty at night and serving as a runner from post to post when there was an action in our neighborhood. We learned how to crawl, shoot and fight, and we also administered first aid and cooked for the soldiers who were sent into battle. In the interim, I studied Hebrew and Jewish subjects.

Jerusalem was hungry. Months would pass before food or vegetables came into the city. We had no gas or kerosene with which to cook, so our boys took turns in chopping wood for our outside, crudely-built stove. We were constantly scavenging for anything green growing in the fields which we would put into pots and call soup. Bread was in short supply, and we served it on the table two or three days after it was baked – which killed our appetite. It was served with some brown, sweet unidentifiable goo, since there was no jam or margarine.

My brother Artie showed up to fight in the war. He had brought a small salami from the U.S. and saved it throughout his training in France to bring to me, his little sister, in besieged Jerusalem. That Shabbat, the entire group enjoyed the first taste of meat in months – a paper-thin slice of salami.[3]

Water was also rationed in Jerusalem. All private wells were locked, and a brave group of water deliverers went about the city each day, through the bombs that fell incessantly from Nebi Samuel, distributing water – one jerry can to a person. This water was used for drinking, cooking, washing dishes and clothes and flushing the toilet. We became experts at using the same water for different purposes. I don’t think the drain under the sink was put back for months. On Friday we treated ourselves to a bath by pouring half a can into a basin and standing in it, splashing ourselves carefully.

I was the only English-speaking person in the group, but hadn’t spoken a word of English for about eight months, until Artie came. I remember then struggling to recall simple English words. I learned how to get along with my Israeli and European classmates, and learned a lot about human nature, being in charge of the guard duty schedule.

I had a warm fur-lined leather jacket which hung in the hall and served the one on guard duty. I also had a Hallicrafter short-wave radio which was taken along by the thirty-five students who left from our house to go into the Judean hills to save Gush Ezion, and were massacred. From our house we could hear the bombs and see the bullets flying and knew the Gush was falling. From our house we watched the fires in the Old City and saw it fall. On the hill opposite us, looking westward to where Hadassah Hospital is now, the Jordanian tanks patrolled back and forth while we stood guard with two rifles and a sten gun – an old type gun which goes off on its own at unexpected moments but never when you need it. We were all sure we would die and that the end would come soon.

After the war I went back to the U.S. to earn more money and marry the boy I had left behind. We returned to Israel three months after the wedding to begin our life together in Jerusalem. During those first years I would look out over my balcony and see young families going to their relatives to celebrate festivals together. I envied them and cried a lot. But as time passed, my own family grew, and my brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews, cousins, aunts and uncles came to live here, and so did our parents and my grandfather. I was the first to arrive; today we are hundreds.

Adapted by Judy Shapiro, Chani’s niece – whose love of Israel and eventual aliyah was, in great part influenced by her aunt whose pioneering spirit reached mythic proportions in her family – from a talk given by the author to Amit Women.

[1] The GI Bill of rights was enacted after WWII, giving education benefits to American army veterans.

[2] The Liberty ships were cargo ships built in the U.S during WWII. They were cheap and quick to build, and came to symbolize wartime industrial output.

[3] Artie, now living in Tampa, Florida, adds: Washington officials did not permit American citizens to travel to Israel at the time. My mother asked me to bring Chani back. I enlisted with a group that was recruiting volunteers for the Israeli army. We shipped out of New York in an old freighter, landed in Marseille, were transported to a wooded area and given two weeks’ training on how to load, shoot and clean Czech rifles. In Le Havre we picked up 100 Holocaust survivors, set sail on an Italian freighter, eluded the British Navy (Rabinowitz, The Jerusalem Post journalist was caught and spent the war in Lebanon). The Italian crew got drunk the first day out of France and Sam Lipsky, my friend and fellow passenger who had been in the American Navy, steered the ship from France to Tel-Aviv. (Sam was later instrumental in getting the Israeli Navy started). Our boat crash-landed off the Tel-Aviv beach and we were whisked away to a kibbutz. Before leaving America, I had carried five radios given to me by folks to deliver to relatives. Two were confiscated by the French authorities, two I sold to fellow volunteers, and one I gave to my father’s brother, Pinchas, who survived the concentration camps and was selling ice cream in the port of Haifa. I had many offers for that kosher salami and for six weeks it never left my side.

THE RABBI’S DAUGHTER - A Review

THE RABBI’S DAUGHTER - A Review  Spotlight on .....Roz Brodie

Spotlight on .....Roz Brodie  ESRA COMPUTER CLUB

ESRA COMPUTER CLUB A new website in English - on Volunteering - Launched in Israel

A new website in English - on Volunteering - Launched in Israel Help Needed for Abused Horses and Donkeys

Help Needed for Abused Horses and Donkeys Heather's Heseg

Heather's Heseg