It took a while until I realized that the noisy cricket on our lounge wall was a constant companion, and that I was actually experiencing ringing in the ears. When I Googled "tinnitus"I found an article by Grant Searchfield, of the University of Auckland in New Zealand, describing how cognitive behavioral therapy was proving useful for ameliorating the phenomenon. Little did I imagine that four years later I would have the privilege of spending five months with Searchfield observing from close up how his clinicians help people with tinnitus and participating with his talented student, Roanna Mowbray, in an experiment designed to improve the options available.

Tinnitus is a phantom sound generated by the brain. The phenomenon is perhaps best illustrated in this diagram: You seem to see grey spots in the corners between the squares — but actually there is just white space. Our fertile brains trick us into seeing an image when in reality there's nothing there.

You seem to see grey spots in the corners between the squares — but actually there is just white space. Our fertile brains trick us into seeing an image when in reality there's nothing there.

In the same way, we hear a ringing in our ears though there is no external sound.

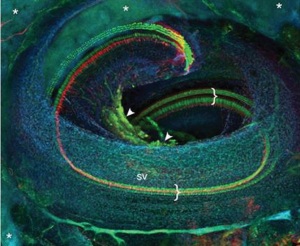

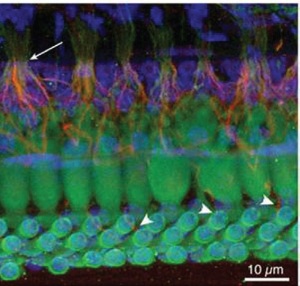

How do we hear normally? The pinna (the visible part of the ear) collects sound into the outer ear canal. The sound makes the eardrum vibrate. The vibrations are passed on to three tiny bones in the middle ear and from them to the snail-shaped cochlea in the inner ear. The cochlea is lined with sensitive hairs that trigger generation of nerve signals to the hearing centers of the brain, where they are translated into the perception of sound.

What happens to hearing as we age? The cells of the sensitive hairs are arranged like the keys of a piano. Each cell responds to a certain frequency of sound and sends a defined signal to the brain. Thus we normally hear a range of sounds from low to high pitch, measured as 20 to 20,000 Hertz. But as we age, hair cells start to die, particularly those that respond to the high frequencies above 8,000 Hz. Usually tinnitus occurs when we have hearing loss and nerves in the brain’s hearing centers that have lost their neural input produce a perceived sound even though there is no external signal. Age-related hearing loss affects us all, but only about 25% of people with hearing loss experience tinnitus. This indicates that other factors are involved too, but the factors that predispose certain individuals to tinnitus are not yet known. Tinnitus is also common in people exposed to loud noise, in an industrial setting or during military activity. Acute exposure to very loud noise, as in a discotheque, frequently gives rise to ringing in the ears that disappears after a day or two. However, sometimes the tinnitus becomes chronic. In rare cases, physical pressure on the auditory nerve can cause tinnitus and this can be diagnosed by the audiologist.

Tinnitus can cause stress, affect the quality of sleep, and reduce our ability to concentrate and function at work. The international clinical and research communities have established a standard questionnaire in which individuals describe the loudness of their tinnitus and its intrusion in their lives. Responses to the questionnaire that are being collated into a worldwide database indicate two salient findings:

1. When people are asked to match the loudness of their tinnitus to an external sound provided through headphones, there is little correlation between what they perceive as the loudness of their tinnitus and the actual volume of the sound.

2. The level of distress caused by the tinnitus or the ability to cope with it has no correlation to how loud the tinnitus seems to a person or how annoying it is.

When we hear a sound, our ears determine where it's coming from and our brains tell us what's making the sound (for example, car hooter, thunder, baby crying). Even in a crowded room full of chatting people we can pick out our name being called and also concentrate on a single conversation, putting all the other voices into the background. This is known as the "cocktail party effect". Current research indicates that in tinnitus the brain shows auditory activity even in the absence of a signal from the auditory nerve and this leads to perception of a phantom sound. Therefore, tinnitus “loudness” can be understood as the amount of attention we pay to the tinnitus network: The more we are aware of the tinnitus, the louder the perceived sound. Indeed, brain imaging studies show activation of emotional, cognitive, and memory networks in tinnitus, and these findings explain the symptoms of frustration, annoyance, anxiety, depression, irritation, and concentration difficulties that accompany the perceived severity of the tinnitus.

So what can be done about tinnitus? Current therapies include cognitive behavioral therapy, in which the audiologist explains the basis of the tinnitus, combined with delivery of an external relaxing sound to mask the tinnitus. Current sound-relief therapy is based on psychological theories of attention, suppression and habituation and are designed to deflect the focus of our attention from the phantom sound to a real external sound. By making an external sound the focus of attention, we hope to force the tinnitus sound into the background and teach our brain to ignore it.

People are most aware of their tinnitus in a silent environment, particularly at night before they drop off to sleep. Therefore, at the most basic level, one can listen to music during the day, and at night use a pillow cushion to hear the music at a very low volume. Carefully designed experiments with volunteers indicate that relaxing natural sounds, such as rain or waves breaking, are effective in relieving the distress associated with tinnitus. Devices that attach to the ear can be used to deliver the music during the day. When hearing loss is associated with the tinnitus, hearing aids that restore the lost high-frequency input are very effective: Restoration of a genuine signal to the nerves of the primary auditory centers is thought to reduce their engagement with the tinnitus brain network. Masking sounds that overlap the tinnitus frequencies determined for each patient can be delivered through the hearing device. Usually patients report considerable relief of their tinnitus over time.

Extremely incapacitating tinnitus, experienced by a small percentage of sufferers, may be treated with protocols aimed to reset the tinnitus brain network. Treatments under development include transcranial stimulation, in which electrodes are attached to the left side of the head above the primary auditory center and to the forehead to deliver a very low direct electric current or magnetic stimulation. Pilot studies indicate positive results for some patients, but further studies are required to establish useful treatment protocols and to assess which patients have the most chance of benefitting from the treatment. Drugs that reduce stress or that could block the interaction of the tinnitus brain network with the stress response are also being tested. Given the amazing progress in our understanding of tinnitus over the last decade, there is every reason to hope that the next decade will see considerable advances in treatment options.

For further information I highly recommend the Tinnitus Research Initiative website, http://www.tinnitusresearch.org/, where you can find a link for patients. Please be careful about treatments you see advertised on the Internet, as there are no known natural cures, food supplements don’t help, and not all the gadgets promoted there are useful.

Milestones 168

Milestones 168 “Be our Guest” at Beauty and the Beast

“Be our Guest” at Beauty and the Beast Advertisers List

Advertisers List Yad Sarah's new house in Raanana

Yad Sarah's new house in Raanana English speaking Feldenkreis

English speaking Feldenkreis Men don't Make Passes at Girls who Wear Glasses

Men don't Make Passes at Girls who Wear Glasses Dina Raveh

Dina Raveh