Happy Memories of My Father Jack Luck

I still cannot believe that you, Dad, are no longer here. It seems like yesterday that your smiling face was with us. You were joking with the adult members of the family and telling stories, as you always do, to your great-grandchildren. You lived in the East End of London, as the majority of Jews did at the turn of the century, until 21 years later when, on May 30, 1939 you married 18-year-old Rachel Warman in Antwerp, Belgium. Your visit there in 1937 was the start of that very special relationship which brought the two of you together. That special bond existing between you and Mum was not often found in couples. It was unusual to spend so much time together and even though you were married for more than 70 years you were never of tired of each other's company. You were a loving husband, an inseparable partner.

Somebody only had to pass you in the street, and if they looked in any way miserable you would get them to unburden themselves, thus making their load much lighter to bear. Even when in hospital and the nurses would enquire, “How are you?” you would always answer, “I am fine and how are you?” You had helped them without realizing it. Dad, I had often wished I was like that.

From our childhood days we were taught that everything was possible. How you kept warm especially during the war years. You always managed to find a piece of cardboard to sit on instead of on the stone seat. “You can make do on improvised toys and games without spending too much pocket money. You just need to put on your thinking cap, for it to cost very little,” you used to say. Neither you nor your friends could afford a football, so you crumpled up newspaper tightly and tied it around with a piece of string. "Beggars can't be choosers,” I remember you saying and, "If you don't have any socks you can't pull them up." These expressions you would often use later on in business and certainly when it came to educating your children: “Don't spend more on a product than you can afford.”

For you, Dad, this was the case when you were growing up. It applied to swimming, which you liked a lot. Your parents, like most others, could not afford the one penny for their boys to swim in the local swimming pool. So instead, you swam in the canal and dried yourself with the corner of your shirt which did the job almost as well.

Time was passing by and you were growing up. It was in 1939 when the Second World War broke out and you were called up into the British army. This saved Mum's life, as straight away she became a British subject. You learnt so much from those tough six years. Three times you were caught by the Germans and imprisoned, but being a very determined person you always managed to find ways of escaping. Sometimes you were out for days. You met people who were kind to you, but you never did reveal that you were Jewish. There were some who gave you a hot meal whilst others allowed you to sleep in their homes. You often told us of the straw bed you slept on and how its smell lingered on for days. The worst occasion was when you were in a labor camp and 30 men were needed to do some manual work. Nobody had volunteered, and so you were one of those chosen to go to work. The Germans were going to make you use camphor which did have an effect on your skin. It was certainly not a case of Luck by name and sometimes by nature. Though you had protested, it was no good. You had answered back and as a result were shot. I could never get over how strong you were to survive this ordeal. Firstly you were operated upon in a German hospital and afterwards in a British one. Though one kidney had to be removed you did, in time, pick up your strength.

After the war you went into the same business as your father. It was buying and selling rags and scrap metal. Remember, Dad, how you considered Mum a great partner? You had confidence in her running the shop so that you were able to drive around in your 10-ton open lorry buying non-ferrous metal. Since she had helped in her parents’ grocery shop, she had the necessary experience behind her. At first you lived above the shop and then afterwards moved to East Finchley, in North London.

You made aliyah to Raanana in 1975, having taken early retirement. Your plan was to travel the world with as little baggage as possible, “one on one off”, as you called it. Mum and you were very adventurous and you knew exactly where to go and how to begin your travels. It always seemed as though you would find the most obscure places to visit, and this was done by throwing a dart onto a very large dart board. Wherever it landed you went. Do you recall how your trips started? On arriving in a town, you would go to the town hall and pick up information on hotels, places of interest and transport. One thing you never did was to travel by taxi. You wanted to get the feel of the local people, and the way to do it was to go by bus or train. You would talk to the people and even though you could only speak English, you would find a way of making yourself understood, and with Mum's six languages you were well away. You always discovered a beauty spot that perhaps the town hall hadn't told you about. One thing that was very important to you apart from the cleanliness of the hotels and the bed linen, was the toilets.

It amazed me how, in places where it was written in the guide book that there were no Jews, you seemed to find them, however few there actually were. One incident I remember you telling us about was the time you and Mum were on holiday in Fez, Morocco. On Shabbat you went to shul and started talking to a Mr. Cohan. He duly invited you back to his home for lunch, assuring you that it was kosher. One thing he did say was that at 1pm every Shabbat his brother would phone from Haifa. Apparently, since there were no ties between Morocco and Israel, only on Shabbat could a conversation be had.

In England, at Christmas, you once visited King's College University with friends. It has the most beautiful Gothic architecture. The choir was made up of boys who were singing common carols, and what was your comment? "There's nothing like a good, heimisha shul.”

At around the same time Miriam and I were going to “cheder” (Hebrew class) which was in the local shul. Dad, do you remember giving us a lift in the lorry and picking up other children on the way? Of course we were convinced that you would allow us to stand with the other children in the open part of the lorry, shouting and waving our arms, but no such luck. Even though you would be driving at a snail's pace, your children had to be by your side for safety so that you could at least keep an eye on us. We all had to alight at the shul. That was the rule. There was one boy who thought he could fool you by remaining on the lorry, and Dad, do you remember what you did? Return home, to our home, with him furious with you.

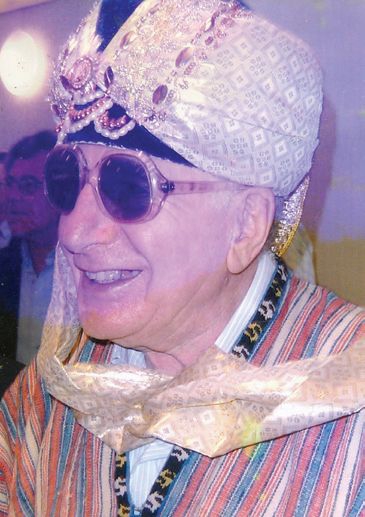

I remember how, when you came on aliyah, you searched for voluntary work. You would walk along Ahuza Street and "spy out the land”. You loved to be with people and did find work in an institution for mentally retarded children. Though you were a driver picking the children up from their homes and taking them to the center you were thrilled when any child made the slightest improvement. When you worked with adults there was one lady, Shira, who was always there for you. In fact she considered herself the one and only one. One day there was a trip, Mum came along and sat by your side on the bus and as soon as Shira saw you sitting together, she demanded, in her limited Hebrew, that Mum moved. Of course Mum didn't, and as a result, it took a while for Shira to calm down and a long time before she would talk to you again. You were always an eccentric person. Not so long ago at a shul Purim party you dressed up, wearing a turban and a thick coat with a belt, all bought in Tashkent. You were the life and soul of the party. When children admired your outfit your face told everyone, "I am a king". I loved the mink bow tie you acquired from a piece of Mum's mink, which you wore frequently to weddings.

You were a truly wonderful person; a very dear husband, a wise father, grandfather and great-grandfather to many children. You often felt that you needed a banner announcing the number of great-grandchildren you had. Two more great- grandchildren have been born, both girls and who knows, by the end of the year, how many more?

Slowly but surely your family is helping to make up for the six million who perished at the hands of the Nazis.

My memories of you, Dad, took a lot longer to write down due to the sadness I felt at remembering the different aspects of your life and how they affected me personally.

I miss you dearly and will always love you very much.

Let’s have a bit of Playback

Let’s have a bit of Playback-1372659501.jpg) Buying New Construction in Israel

Buying New Construction in Israel A lot of hot air - ballooning

A lot of hot air - ballooning Bridesmaid recalls a very special day 59 years ago

Bridesmaid recalls a very special day 59 years ago Harry Berman

Harry Berman Sam Levin

Sam Levin