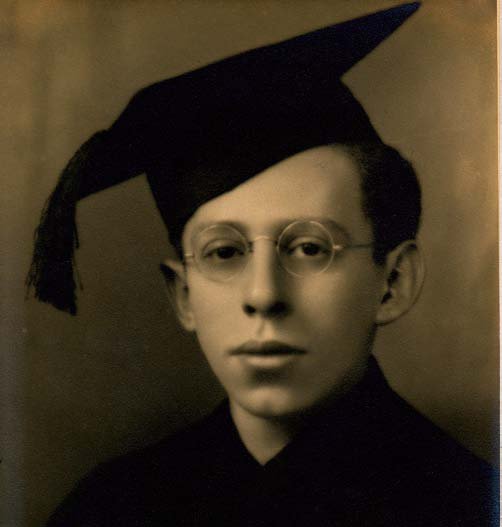

In 1923 my father, Gershon Marinbach, arrived in the United States at the age of nine with his parents and older brother from Gomel, Russia. Like most immigrants, it was easier for the children to adjust than for the parents who worked hard to put bread on the table. Many parents sacrificed their own ambitions so that their children could have advanced education. My father recognized and appreciated this gift, and this tender story is a tribute to his father. It was originally published in AUMNUS, City College New York, Summer, 1991.

Judy Shapiro

One day in the Fall of 1932, I stood in awe before the arched, carved gates on Convent Avenue, the entrance to City College, and as I crossed its threshold onto the campus, I uttered the traditional Hebrew blessing, thanking the Lord for this event that had happened in my life.

My having been admitted to the tuition-free City College on the basis of my grades was a triumph not only for myself but ever much more so for my father. Our family had arrived in the United States on November 1, 1923, the last of a group to be permitted to leave the Soviet Union, and when we were met at Ellis Island by my father's brother Sam, who sent us the visas and the transport tickets, all the possessions that we had brought with us were trapped in a bed sheet. (Classified as bourgeois because he was the owner of a leather-goods store, my father was sent to a labor camp for a re-education when he protested the nationalization of his business.)

My father's formal education had taken place in a typical religious heder, where he learned Torah and Talmud. In addition, he had had a tutor who taught him how to read and write Russian and to do some simple arithmetic. After that, all the education that my father received was through reading the newspapers and as many books and periodicals written in Yiddish, in Hebrew and in Russian that he was able to get his hands on. His great sorrow was that, as a Jew living in Czarist Russia, he was not even able to dream of his being admitted to a "gymnasium" (high school) and more so, to a university. He had not been among the lucky ones born into rich Jewish families who hired private teachers to prepare their children to pass the entrance examinations to the gymnasium, and to possibly ease their way in with a bribe. As for admission to the university, with a few exceptions Jewish men had to leave Russia and to study abroad.

In America, as a mature man and a father of two, the attempt for him to master the English language was a difficult one. The transfer from the Cyrillic alphabet to the Latin was confusing. Also, after a hard day's work as a presser in a sweat shop, it was not easy to keep his eyes from closing when he sat down to learn English at evening school. Fortunately for his continued self-education, the lower East Side where we settled was a boiling cauldron of cultural life, steaming forth in the Yiddish language. There were five Yiddish dailies and as many periodicals. The Seward Park Library, on East Broadway, was lined with books of world literature translated into the Yiddish language. The Educational Alliance, across the street from the library, offered public lectures, forums and discussion groups, all in the Yiddish language. Second Avenue had five live theaters with performances in Yiddish ranging from musicals to Shakespeare plays. Radio Station WEVD broadcast Yiddish programs daily. There were synagogues with their charismatic rabbis and world-renowned cantors, and the "landsman-shafts" (societies of townsmen). They provided social affairs for their members and offered them loans and financial aid in times of need, and they provided burial grounds when death occured. As long as one did not step out of the boundaries of the Jewish enclave, one could get along very well without English.

My father took a keen interest in our studies, encouraging us to discuss, at the Sabbath table, that which we had learned during the past week at school. For his part, he would tell us stories from Russian history, about the Crimean War, the Russo-Japanese War, and of his own experiences as a soldier in World War I. Of course, he had many vivid tales to tell about the Revolution which followed. It was from him that I acquired a love for history, which led me to take the subject as my major in City College.

On Sundays and holidays, my father would take the family to visit and explore different parts of the city. One time it might be to a museum, another to the aquarium or to picnic in one of the New York parks or to swim in the waters of the public beaches. On the day the Holland Tunnel opened we were there with the crowd that crossed the Tunnel from New York to New Jersey on foot.

It was at great sacrifice that my father sent me to the day session of City College. At that time he was earning $25 a week. When I proposed finding some work during the day and attending the evening session of the College, he would not hear of it.

Life at City College was very competitive, and the scholarship was at a high level. It took a great deal of work to maintain high grades. Knowing my father's interest, I would tell him about my courses and about some of the outstanding scholars of the faculty; men like Morris Raphael Cohen, the renowned philosopher, the pride of the college, sharp, caustic, and worshipped by the students. Father drank in every word.

In the garment industry in which my father worked, there were not four, but five seasons: the spring season, the summer season, the autumn season, the winter season, and what they called the slow season when workers were laid off. It was in one of these slow seasons that I came home one afternoon from school to find my father sitting in his favorite chair with a newspaper in his hand. I could see that he was not reading. His eyes were gazing at the wall and the expression on his face told me that he must be worried about how he would manage until he would be called back to work.

Impulsively, I said to him, "Pappa, how would you like to go with me tomorrow to school?"

My father let his paper fall to his lap and he asked, "What did you say?"

I said again, "Pappa. How about going up with me to City College tomorrow?"

He thought for a while and replied, "Would you not be embarrassed?"

"Pappa," I said to him, and took his hand into both mine, "how could you say that? Don't you know how proud I am of you?"

The next day, dressed in his Sabbath suit, my father accompanied me on the long ride on the 7th Avenue line from the East Side to the 137th Street station on whose wall was tiled in bold letters the sign, College of the City of New York.

As we went up from the subway, we were greeted by several students handing out leaflets. I read the leaflet given to me, and I explained to my father that this was a notice calling for a student demonstration against the R.O.T.C. which was a voluntary course which trained students to become reserve officers in the United States Army. The students who were distributing the leaflets were members of a peace movement which advocated world disarmament as an end to settling disputes between countries by war. My father commented that these students were evidently well-intentioned young men but quite naïve.

"The world," he said, "is not yet ready for this, not for a long time to come. Just watch that little man with the moustache in Germany," he said with a sigh.

We toured the campus with its impressively Gothic buildings that exude an air of ancient learning, and then I took him to the library where I left him to read the book which he had brought with him, a history of the American Civil War written in Yiddish. When I returned after my first two classes, I took my father with me to my third class, "Music Appreciation." We walked through the imposing main building into the Great Hall, resembling a cathedral with its vaulted ceiling, majestic columns and Gothic windows. A little while after we took our seats in the back of the hall, the door on the side of the stage opened and in walked a man of short stature with a shock of white hair. It was Professor Heinroth. Sitting down at the organ and placing his hands on the keyboard, he made the walls of the hall vibrate with a Bach composition. I gazed at my father, and his mouth was slightly open, his eyes shining and filled with wonder.

Our next visit was to the gymnasium to watch our basketball team practicing, coached by the well known Nat Holman. City College was very proud of its basketball team which performed well and scored impressive victories. Our students, all city boys, living in wall-to-wall tenements with no open spaces in which to develop any significant skills in baseball and football, were pushovers for the teams of other colleges. There were, however, many gymnasiums in the settlement houses, and enough city parks in which we were able to play basketball and develop good teamwork. I explained the game to my father, he was amused by the way the players dribbled the ball, passed it gracefully to one another shooting for the basket.

We ate our lunch, which we had brought from home, in the park off the campus, and we went along together to my last class. It was a lecture in philosophy by the charismatic, eloquent, scholarly and witty Professor Harry A. Overstreet. Introducing the Professor to my father, I asked him for permission to have my father sit in on his lecture. We again sat in the back of the lecture hall, and as Professor Overstreet spoke, I jotted the notes in Yiddish for my father to read.

All the way back home my father was quiet. He responded to my attempted conversation with a "yes" or a "no" or a silent nod. After a while, he looked at me, smiled, and said, "Thank you for a wonderful day."

Israel: Reclaiming the Narrative - A Review

Israel: Reclaiming the Narrative - A Review ESRA Outing to Aida at Masada

ESRA Outing to Aida at Masada  Coffee Group for Immigrants enters 5th year

Coffee Group for Immigrants enters 5th year (302x450)-1451381711.jpg) Odeon Oscar

Odeon Oscar The Jewish Connection

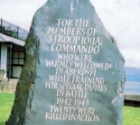

The Jewish Connection ellis island

ellis island