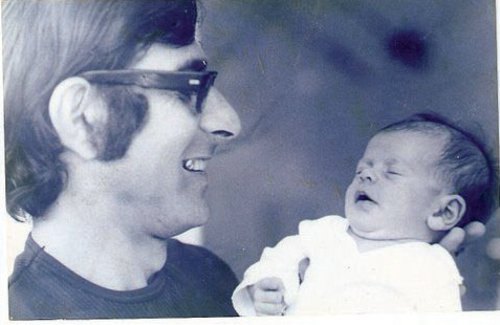

Andrei Spitzer with his baby daughter, Anouk.

The opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympic Games was an amazing spectacle enjoyed by millions of people worldwide. But for relatives of the 11 Israeli athletes murdered by Palestinian terrorists at the Munich Olympics in 1972, there were only the sadly familiar feelings of dejection and anger as it became clear that this Olympic ceremony, like every other since the massacre took place, contained no official memorial for their loved ones.

This year, due to the power of social media, the families’ campaign gained more momentum and international support than ever. Calls for a minute’s silence came from numerous governments and politicians, and 110,000 people from 155 countries signed a petition. Dutch-born Ankie Spitzer, widow of murdered Israeli fencing coach, Andrei Spitzer, has been at the forefront of the bereaved families’ 40-year campaign to have just one official, public remembrance of the atrocity. Together with Ilana Romano, whose husband, Yitzhak Romano, was another of the 11 Israeli victims, Ankie met Jacques Rogge, President of the International Olympic Committee, just before the start of the Olympics and presented him with the petition. “Despite the fact that Rogge is also from the Netherlands and was himself an athlete at the Munich Games, it was clear that he remained unmoved,” she says. “He told us, coldly, ‘I’m not going to do it’. Ilana and I got up, gathered our things and left.”

Ankie met Andrei Spitzer at the national fencing academy in the Netherlands. He had come from Israel for further training as a fencing master and she was one of his students. They married in 1971 and lived initially in Biranit, a small sports academy that specialized in fencing, situated right on the Lebanese border. “It was in the middle of nowhere but Andrei and I had a wonderful year there. It was the happiest time,” she recalls.

In August 1972, Andrei flew with Israel’s Olympic team to Munich. Ankie took their seven-week-old baby daughter, Anouk, to her parents in the Netherlands and then joined Andrei, who was Israel’s top fencing coach.

“The Israeli athletes were so excited to be at the Olympics,” she says. “I recall in particular how struck Andrei was by the openness of the Olympic Village. He made a point of speaking to athletes from Lebanon and shaking hands with them, and he was delighted when they reciprocated. He said that’s what the Olympics were all about.”

The memory of the horrific violence that shattered such innocent idealism has kept the families fighting for justice all these years. They have been rebuffed by the International Olympics Committee every time, with various reasons cited. In Montreal in 1976, for example, they were told that 21 Arab countries would boycott the Games if there was an official commemoration. In Atlanta in 1996 they were told there was no Olympic protocol for including a memorial at the opening ceremony.

Although Spitzer was upset by Rogge’s blunt rejection this year, she doesn’t view it as a failure. “If I look back over the five months of intense campaigning, I feel we had a huge victory. So many memorials, minutes of silence and other moving gestures took place in parliaments and in the Jewish world. I have two huge folders with signatures and messages. There were 10,000 newspaper articles. The world was reminded, so in that sense the campaign was a success.”

For the tenth time in four decades, she put everything on hold while she lobbied the International Olympic Committee and it is only now, three months after the London Games, that she feels re-energized and ready to resume her life. She is a journalist and television correspondent in Israel for Belgian and Dutch television. “I’ve been living out of a suitcase for months and I’ve finally put it away in the loft,” she says. “Now I can spend more time with my family, and I’ll be reporting on the Israeli elections.”

But as the 2016 Games get closer, the campaigning will begin again. Incredibly, even after 40 years, Spitzer says the bereaved families still have the will to keep fighting. “We hoped so much that we wouldn’t have to go to Rio, but there has to be an acknowledgement in the Olympic framework of what happened. In 1972, Israeli athletes went to the Olympics in peace and 11 of them came back in coffins. We have come to believe after all these years that this is discrimination against Israel and Jews. But we will carry on our campaign, and our children will carry on when we can’t any more, until the IOC marks the Olympics’ darkest day publicly and appropriately. They are not rid of us.”

Chanukah 5773

Chanukah 5773 The Guild launches its season with The Fantasticks

The Guild launches its season with The Fantasticks My Chanukiah

My Chanukiah A Matter of Perspective

A Matter of Perspective A fantastic motor sport adventure – a dream come true

A fantastic motor sport adventure – a dream come true my sporting year 2007

my sporting year 2007 Marian Lebor

Marian Lebor