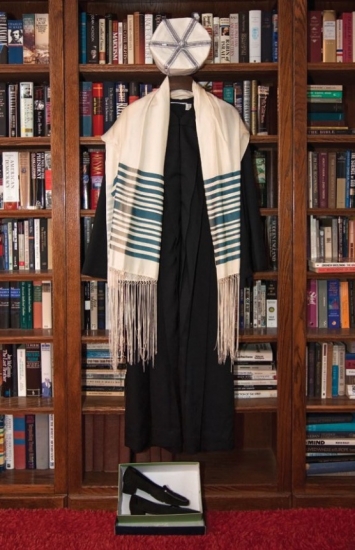

The Rosh Hashanah robe of Cantor Irving Schock, Annette Keen’s father, and the box with the shoes she wore to his funeral. Photo: Dr. M. Richard Mendelson

“Liberator, Rescuer, Sustainer and Merciful One in every time of distress and anguish, we have no king but You. God of the first and of the last, God of all creatures, Master of all generations, Who is extolled through a multitude of praises, Who guides His world with kindness and His creatures with mercy.”

I was a little girl when my father chanted these excerpts from the Nishmat prayer over the tiny grave of my first pet, crushed under the wheel of an oncoming truck. Like all truly effective teachers, father taught less by what he said and more by what he did. Like all truly earnest seekers after God in a fallen world, he created out of his own longing, islands of holiness; magic circles where faith trumped doubt and God kissed the heart of His sorrowing children.

Father had become a farmer by default. He had survived the Holocaust and immigrated to New York City. But its noise maddened him. Then serendipitously, he discovered a little farm community in southern New Jersey, where other Jewish refugees had found refuge from the torment of memory and the bustling of the city. In the peacefulness of his own bit of land, in the routine of farm life, the former yeshiva student, scion and sole survivor of a long line of scholars and cantors began to recover and nurture his will to go on.

He tended his farm, raised his family, and in the leisure hours that farming allowed, he pored over his books, the Chumash and Talmud, and indulged in the great joy of his life, cantorial singing. My earliest memories of childhood ring with song. When my mother sent me out to find my father, I followed the sound of singing with a retinue of pets in tow.

Our cats and dogs roamed freely over 25 acres of lush forest that surrounded our farmhouse and chicken coops. These were farm pets, that is, they were not allowed into the house, an attitude my European parents brought with them from Poland. The pets were loved, but not pampered in the American way.

Our kittens and puppies arrived from the usual source, a litter from another farm. They lived together in a large shed, where they slept and took their meals together, without enmity.

The pets had only one common enemy, the occasional car and delivery truck that raced along the usually quiet country road. Even though our house and farm were recessed from the road, still, the animals ran free, and we suffered one fatality, which broke my heart. It was my first puppy.

I was 8 years old when it occurred, and I can still see the little mutt in my mind's eye, more than 60 years later. He had run right under the wheel of a delivery truck, and the driver, no more than 19 years old himself, was devastated.

As my father and I ran towards the road, the young fellow approached, the broken body of the puppy cupped in his trembling hands. “I couldn’t brake fast enough,” he said, his voice shaking as much as his hands. “It’s okay,” my father said, in his heavily accented English. “It was an accident.”

Father carried the pup and the young driver carried me, pale and speechless, up to the animal shed, where in silence, my father gently laid the puppy into a little box. In a sad procession, the young driver and I followed my father up to a little grassy hill, and beneath a towering oak my father dug a hole and buried the box.

There we stood, in the clusters of grass and moist black soil upturned by the shovel, the stricken young truck driver, nearly as traumatized as I, as my father recited in Hebrew the prayer at the beginning of this article:

“Podeh u-matzil umfarneis umracheim b'chol et tzarah v'tzukah, ein lanu melech ela atah. Elokei harishonim v'ha-acharonim, Elokah kol b'riyot, adon kol toladot, ham'hulal b'rov hatishbachot, ham'naheg olamo b'chesed uvri-yotav b'rachamim.”

Walking back down the hill to the house, I noticed the dirt from the pup's open grave clinging to my sneakers. As my father watched solemnly, I removed them carefully, and placed them in a shoe box. I never wore them again.

I don’t know why I did this, but my father never questioned it. It took a lifetime for me to understand what he had understood: the need to remember and to memorialize. He knew the sacredness of grief and loss, and the longing for God that makes it so.

Father died 14 years ago. When I returned home from his funeral, my mother gave me a wonderful gift - the long black cantor’s robe my father wore when he led the Rosh Hashanah service at the little synagogue he and other refugees had built for themselves. The white robe that he wore on Yom Kippur my mother kept for herself.

Father’s Rosh Hashanah robe now hangs in the corner of my study, under a protective plastic covering. Just above it is a photograph of my father. He is wrapped in his prayer shawl, his tallit. With one hand pressing the wall of a memorial established in Jerusalem for martyred Jews of his Polish town, he prays for his obliterated family.

When a breeze blows through the open window of my study, fluttering the skirt of the Rosh Hashanah robe, you can spy a box I placed there 11 years ago. In it are the shoes I wore to my father’s funeral. To them still clings the dirt from his open grave. I never wore them again.

Milestones 168

Milestones 168 “Be our Guest” at Beauty and the Beast

“Be our Guest” at Beauty and the Beast Advertisers List

Advertisers List (302x450)-1451381711.jpg) Odeon Oscar

Odeon Oscar The Jewish Connection

The Jewish Connection ellis island

ellis island Annette Keen

Annette Keen