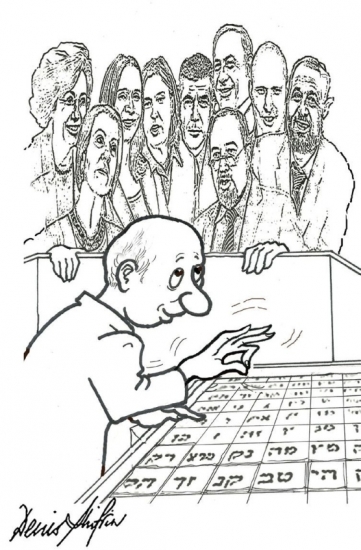

Illustration by Denis Shifrin

By the time you read this, the elections will be over and we will have chosen the men and women who will decide for all of us how life will be in this peculiar country for the near future. I say peculiar, because we still haven’t decided who we really are. We are Zionists, non-Zionists, post-Zionists, religious, secular, extremists, moderates, socialists, capitalists, democrats and unabashed non-democrats, Jews and non-Jews, ethnically diverse, with innumerable opinions, values, ambitions, hopes and fears. Most of us share the desire to live in a Jewish state, but we haven’t decided who is a Jew and what it means to be Jewish. We claim to be politically aware but many of us don’t have a clear understanding of all the political issues. We claim to care about what will be, and yet most of us do nothing about shaping our future. We disagree with each other about such fundamentals as why the State of Israel was established, how it was established, what it exists for and how it should be managed. We are subject to doubts and fears, we are unsure of ourselves and of each other, we are inclined to talk rather than to listen, and we have little faith in those we choose to lead us.

This general indecisiveness seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon, reflected in voter turnout at election time. Voter turnout for the first 15 Knesset elections averaged 80%. Voter turnout in the last three elections averaged 66% (excluding the 2013 election as these words were written before it). It is depressing to note how the enthusiasm of the 1950s has turned into the apathy of the 2010s. More and more Israelis are being turned off by politics and politicians. We can’t decide for whom to vote, we are unimpressed by all the party leaders, we know that coalition considerations will overcome ideological integrity and we aren’t convinced that our vote will make any difference, so many of us don’t even bother to go to the polling stations. Those who turn out in force are those who are non-compromising, self-righteous and convinced that their way is the only way. For want of a better word, I will call them “non-compromisers.” The rest I will call “moderates,” and they are in disarray.

The democratic process should ideally produce a government of the majority. But let’s take an example and assume that the electorate is split between 20% non-compromisers and 80% moderates. Let’s also assume that 90% of non-compromisers and only 50% of moderates actually go out to vote. The Knesset would then be elected by 58% of the electorate, but that 58% is made up of 31% non-compromisers and 69% moderates. This would translate into 37 Knesset seats for the non-compromisers and 83 Knesset seats for the moderates. In other words, the non-compromisers would receive representation out of all proportion to their relative share of the electorate (37 seats instead of just 24 seats), and vice versa (83 seats for the moderates instead of 96).

Although 66% voter turnout in Israel is about the same as that in the United Kingdom, one might have expected a lesser degree of voter apathy in this much younger democracy. The issues in Israel are far more fundamental than the price of cottage cheese. The fabric of Israeli society is affected by the relative political power of the religious and the secular. National and personal security is directly influenced by the policies of those who control the Knesset. Freedom of thought, freedom of speech, freedom of behavior, the very cornerstones of a democratic society, may be seriously endangered by a non-compromising minority holding a disproportionate percentage of seats in our parliament.

My own political opinions may or may not differ from those of the majority in the Knesset, but I have no problem with that either way. If the Knesset is truly representative of the majority of Israelis, then I accept the decision of the people, and I will make my own decisions accordingly. However what I find difficult to abide is the thought that our Knesset may not reflect the true majority in the country, and that a minority may be able to exert undue influence over policy-making in government. There are regular attempts to tamper with the electoral system in order to make it more democratic or more stable, whether by making it less representative of minority interests by increasing the minimum number of votes required to assure a Knesset seat, or by making it more representative of the majority by outlawing extremists on the right or the left. These moves, whether well-intentioned or otherwise, have not managed to make much difference.

It may be assumed that the "perfect" democracy is an unattainable dream. However there is one thing that could be done to improve matters, at a low cost to personal freedom. Voting in Israel should not only be a right and a privilege. It should be an obligation.

More than 30 countries around the world have compulsory voting, and many either enforce it or impose some sort of sanction against non-voters. These include Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Singapore, Turkey, Belgium and Greece. The subject has even come up for discussion in the United States and the United Kingdom. There are arguments for and against. Voting can be enforced by the threat of a fine or disenfranchisement, but it can also be encouraged by fiscal or other benefits. Rather than go into all the pros and cons, including the ways in which such a system could be abused, and safeguards for those with genuine excuses, suffice to say that for a country such as ours, having real existential issues at stake, it would go a long way to ensuring that a vociferous non-compromising minority could not dominate a moderate but somewhat lazy majority. The apathetic would be required to make a decision, which in turn might produce politicians attuned to this massive voting block, and even if their voting decisions result in the casting of blank ballots, this in itself would be a democratic act.

Since most of the non-compromisers probably vote anyway, there should be no objection from the extreme left or right to the legislating of a compulsory voting system. Then those who at present don’t bother to vote would have to drag themselves out of their TV recliners and trudge to their polling station. All those who have voted would then have a perfect right to whine and complain about any government not to their liking, and to think about how to change it next time. Meantime, with voter turnout back to 80% or more, we could all be satisfied that the democratic process is working as best it can.

Milestones 168

Milestones 168 “Be our Guest” at Beauty and the Beast

“Be our Guest” at Beauty and the Beast Advertisers List

Advertisers List A new website in English - on Volunteering - Launched in Israel

A new website in English - on Volunteering - Launched in Israel Help Needed for Abused Horses and Donkeys

Help Needed for Abused Horses and Donkeys Heather's Heseg

Heather's Heseg Ilan Shachar

Ilan Shachar