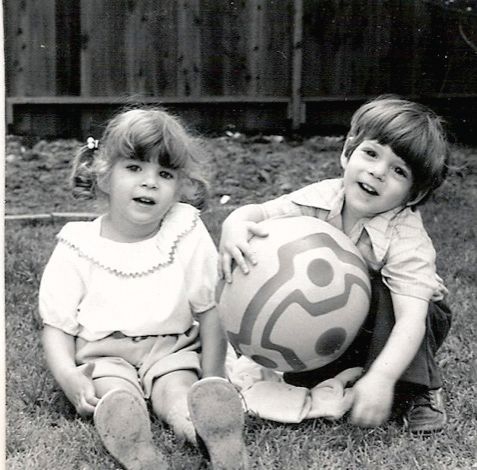

Yael (4) and Eyal (3), 1973, in Rehovot.

An immigrant recalls

It was October 6, 1973. I was 31 years old. Eyal was three, Yael, four. A month and a half previously we had arrived in Israel to this temporary housing, an immigrant absorption center in Ramle, near Rehovot where my husband had work. We had already purchased a flat there and were waiting to move in. The center was located on the outskirts of Ramle, a town founded in the seventh century and many times conquered by different invaders including Turks, British and even Napoleon. Now poor and neglected, it was a place that only those who could not afford better would choose to live.

The absorption center houses were single-storied, small, attached. The one we were assigned was filthy; the family before us had left the house grimy and foul-smelling, and I could never clean it properly. The neighbors on the other side of our flimsy bedroom wall were Americans. He was often drunk, shouting at his wife, usually in the middle of the night.

There were many families from India too. The women wore saris and threw garbage out of the windows into a gulley that ran alongside the houses. Rats slunk by doorways.

How unsettling to see Jews living such a primitive existence. But I knew they would be tended to and taught and in a year or two would be indistinguishable from other Israelis.

Some Iranian Jews arrived after we did. They were wealthy, sophisticated, spoke French and carried large, expensive antelope-hide suitcases. Another family, Holocaust survivors, had blue numbers tattooed on their arms.

When I studied anthropology at university, these were the people I learned about. They were the result of generations of mixing with local populations and the effects of climate that bestowed upon these Jews the features and behavior of the countries into which they had been born. I found these cultural habits fascinating and made mental observations to be recorded in proper anthropological jargon and sent to my professor in the US when I had time.

A World War II child, I was born in the city of New York, where I was punched in the stomach at the age of six by a nine-year-old boy because I was Jewish. I wanted to raise my children without the monster of anti-Semitism breathing fire on our lives. I didn’t want to say to my children, "don't talk so loudly, they’ll know you’re Jewish," as my parents had to me. And the stories of my grandmother in Poland hiding as a child in an attic to escape pogroms still haunted me.

I always knew that I would live in Israel. Throughout childhood and into adulthood I had recurring dreams about walking or flying over the streets of Jerusalem. I was happy I was in Israel, happy to be raising my children here.

This day began as Yom Kippurs usually do, somber, silent, with a special intensity and radiance, but more so because we were in Israel. There were no vehicles moving at all and children played in the open streets. Adults walked in the streets too, unhurried, to and from synagogue, or just for the pleasure of it. The energies were hushed, holy. Most people wore white. Those of us who did not fast, ate quietly and boiled kettles so that the whistle would not shriek. No radios played. Television, black and white, was silent. The sky was a brilliant blue and cloudless. It was hot.

"There is always a heat wave on Yom Kippur," someone told me, "and also on Pesach." On Purim and Sukkot it rains. Weather seems to be determined by holy days. Those living abroad cannot appreciate the connection and are not even aware of it. They celebrate anyhow, but it’s different.

Outside the door, just where the dirt path led to the paved sidewalk, two hawks ambled in that awkward fashion of big birds attempting to walk on the ground. I looked at them and shivered. They stared at me, I walked towards them. They flew off.

Then, late morning, the sputter-sputter of a motor scooter, driven by a young man with a 'kippa' on his head, wearing the uniform of an army reservist, reverberated through the stillness. More cars, trucks, tenders woke up from their Yom Kippur stupor. Then planes - all types, from Pipers to war planes, all flying over hapless Ramle, all flying south.

The multicolored residents of the immigrant absorption center were confused and upset. There is a war, I said. My husband was furious at this remark, but I knew, the hawks knew. The woman with the tattooed number was distraught. Had she survived Hitler only to come to Israel and another war? She sobbed in a Yiddish I hardly understood.

The BBC agreed with me. There was a war. Then the Voice of Israel, at 2 pm, began broadcasting. And we were afraid.

The Iranian immigrants were annoyed and wondered how they could have let relatives here convince them to leave the safety of the Shah’s benevolence.

For three weeks, I slept with the small transistor radio under my pillow. News was being aired every half hour around the clock. And every half hour I awoke, listened and slept again.

There was a blackout. One evening Eyal was home with me while Yael, out walking with her father in the dark, slipped, knocking her head on an iron railing. For an hour I held ice to the egg that had formed on her brow and then it subsided. Afterwards, she came down with severe diarrhea. For days and days we couldn’t get to a doctor. Finally a pharmacist gave us medicine which cured her.

Flour, noodles, eggs and other staples were not available at the grocery stores. The cotton crop was harvested by high school students.

During the war, we moved into our flat in Rehovot, a city of academics and concerts and beautiful gardens that seemed to compensate for our sojourn in dilapidated Ramle.

It was here in our new flat that my parents came for a short visit. They had just bought a flat close to Ashkelon where my brother Aaron, his wife Rita, both 24, and two baby daughters lived, so that when my father retired in a few years they could move here and be near all four grandchildren. Such a joy, four babies in four years.

Aaron (now Ari) had settled in Israel some years before we did. He had received a call-up notice to serve in Vietnam. Certain he would be killed there, he and Rita (Rifka now) had disappeared into the Jewish Agency building in New York and emerged in Israel. University graduates, they settled into a moshav and took up farming, had two sabra girls and were completely content.

It was less than a week after our parents returned to New York. The morning of the cease-fire, before it was announced, two white doves perched on the windowsill. Peace. Birds know about these things. Despite this optimistic augury, the next day, near the Little Bitter Lake in Egypt where Ari was stationed as a medic, a soldier was shot in the hip by a sniper hidden in a tree. Ari and the doctor ran to help him. A bullet entered Ari’s heart just as his left arm was raised; “I’ve been hit too,” he said, and died.

My parents returned. All the other fallen soldiers had been buried before the cease-fire in one ceremony. If anything could have eased the shock to families, that collective ceremony did. But Ari was the only soldier buried that day. My father held my mother up on one side, I held her up on the other. She collapsed, crumpled into her grief. His children were four months old and one and a half. A few days afterwards Rifka received a postcard from Ari: “I’m fine, don’t worry about me. I love you.”

The day after the funeral I must have been ashen because a neighbor asked what was wrong. I told her that my brother had been killed. Her son had been killed in a previous war. Almost every family in this country was mourning someone who had been killed by war at one time or another. This was a country of sorrow to which I belonged by right of my history and determination to be here. In its horrible way, war in Israel where brothers died protecting you and the prime minister called us her children, was easier to bear than the never-ending anti-Semitism of the Diaspora.

I realized then that the war had absorbed me into this country and made me one of these people, so abruptly and absolutely that I could never again look at them, us, objectively as anthropological research requires, could never send my observations from before the Yom Kippur War to my professor in the US. The distinction between me and other Israelis had vanished. I had been transformed into the plural, into us, ours, we.

“You are lucky you have someplace to return to”, my neighbor said, “another passport”. For a moment I thought I hadn’t understood the Hebrew. I don’t know why I didn’t, or couldn’t, reply. Maybe it was so obvious to me that I would stay here forever, maybe the emotions going through me were too difficult to express, maybe I knew I couldn’t explain my feelings in Hebrew or in any language.

Yael on her 5th birthday in Rehovot

This story received honorable mention in ESRA MAGAZINE’s Short Story Competition, “My Israel”, in 2009.

Helen Bar-Lev is an artist and poet. She is Senior Editor of Cyclamens and Swords Publishing, Secretary of Voices Israel Group of Poets in English and Contributing Editor and global correspondent of SKETCHBOOK, a Journal for Eastern and Western Short Forms. She is International Senior Poet Laureate, 2009 of Amy Kitchener Foundation.

ESRA Golf Competition 2012

ESRA Golf Competition 2012 Upside-Down Coffee – for another world. A Review

Upside-Down Coffee – for another world. A Review If I could tell you - a review

If I could tell you - a review A new website in English - on Volunteering - Launched in Israel

A new website in English - on Volunteering - Launched in Israel Help Needed for Abused Horses and Donkeys

Help Needed for Abused Horses and Donkeys Heather's Heseg

Heather's Heseg Helen Bar-Lev

Helen Bar-Lev